1. Separate Place of Residence

2. Provisional Maintenance

3. Provisional Custody

1. Separate place of residence

As explained in the sub-item method, in a few proceedings the consistorial councils decided on a conditional final verdict, which granted one spouse, or sometimes also both spouses, the right to prove their arguments in an additional procedural step. Not all conditional final verdicts included the right to live separately during the evidence proceedings. Some conditional final judgments explicitly ordered the couple to live together. It is noteworthy that in practice it was only women who tried to revise this order to live together, usually by asking the consistory a few days later to grant them the right to a separate residence. The separation or divorce proceedings were also applied for by the women in all cases.

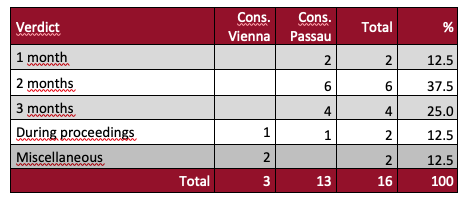

As the table below shows, 13 of the 16 additional proceedings were conducted at the Passau consistory. As a rule, the Passau consistorial councils approved a separate place of residence for only one to three months, in only two cases was it approved for the entire duration of the main proceedings. If there was still no verdict in the main proceedings after this period, the wives had to re-submit additional proceedings for a separate place of residence if they did not want to resume cohabitation.

Table 1 | Proceedings for separate place of residence (1558-1773)

If we put the 16 proceedings in relation to the people, we see that they were carried out by a total of only seven wives. Four women applied for a separate place of residence at the Passau consistory, while three applied at the Vienna consistory.

The overall low number of lawsuits for separate place of residence must be interpreted in light of the fact that only 121 wives and 39 husbands had taken advantage of the right to carry out evidence proceedings and that the vast majority of conditional final verdicts contained the right to a separate place of residence during the evidence proceedings anyway.

In the qualitative analysis it becomes clear that these proceedings were not aimed at giving the wife the right to move to another place of residence. On the contrary, the wives asked the consistory for support so that the husband had to move out of the shared household already during the divorce proceedings. Two of the proceedings date from the mid-17th century, the others from the 18th century. One of the proceedings from the mid-17th century, led by Veronica Hampelin, née Balkenmayrin, widowed Kirchhamerin, gives us insight into the political elite of the city of Vienna.

Veronica versus Joachim Hampeli*n

Unfortunately, a translation is not yet available

Sibylla and Michael Landringer*in

Unfortunately, a translation is not yet available

Case Studies | 18th century

Unfortunately, a translation is not yet available

2. PROVISional Maintenance

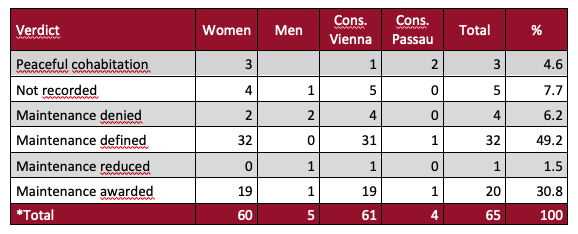

The proceedings for awarding or determining provisional maintenance during the evidence proceedings are quantitively more important, as the provisional maintenance was not decided in the conditional verdicts. The source sample contains a total of 62 claims for provisional maintenance connected to 160 evidence proceedings, which were conducted by 121 wives and 39 husbands. The table below differentiates the additional proceedings for the granting of provisional maintenance between the two consistories and the sex of the plaintiff spouse. It becomes clear that the vast majority of those who asked the Vienna consistory to regulate the provisional maintenance during the evidence proceedings were wives.

Table 2 | Proceedings for provisional maintenance (1558-1773)

Table 2 differentiates the additional proceedings for the granting a provisional maintenance between the two consistories and the sex of the plaintiff spouse. It becomes clear that in the vast majority of cases (90%) it was the wives who asked the Vienna Consistory, and rarely also the Passau Consistory, to regulate the provisional maintenance during the evidence proceedings.

In the vast majority of the cases, it was also the wives who conducted the evidence proceedings. As Table 2 also shows, the consistorial councils rarely turned down requests for provisional maintenance. In almost one third of the proceedings (maintenance awarded), the consistorial councils granted the wives, or in one case the husband, a maintenance title, but did not define the amount of maintenance. The wives could carry out proceedings to determine the amount of maintenance either at the secular courts or at the consistory. As the table also shows, many wives also carried out these proceedings at the consistory. The consistorial councils determined the amount of maintenance in 33 proceedings. In one case, at the husband’s request, they reduced the amount of the provisional maintenance. In three proceedings, the couple agreed on peaceful cohabitation during the evidence proceedings, which we also noted as the result of the additional proceedings. No verdicts could be found for five proceedings (7.5 %).

As described in the menu item norms, an ordinance from October 1753 revoked the consistories’ right to regulate “secular matters”. It is therefore noteworthy that five of the 65 proceedings were conducted in the investigation period from 1772-1783 and that in three proceedings the Viennese consistorial councils awarded the plaintiff wives (Christina Kötzin in 1773, Magdalena Hadaunin in 1775 and Catharina Scheibin in 1778) the right to receive maintenance. In the proceedings of Theresia Perinin in 1774, the verdict has not been passed down and Theresia Luegmayrin agreed on a cohabitation settlement with her husband in 1781.

In terms of gender, it is noticeable that in all the time segments examined, the consistorial councils awarded the wives maintenance almost without exception, while they granted maintenance to only one of four husbands who sought provisional maintenance. The other two men requested a reduction in the maintenance they had to pay to the wives during the proceedings.

Maintenance suits from husbands

In December 1659, Georg Philipp Krafft, as the only husband, was granted the right not only to fetch his clothes and personal belongings from the house, but also to the “proper maintenance” from his wife Veronica, née Burianin. In contrast, the maintenance suits of Christian Wilhelm Freiherr von Willstorf and Joseph Hochenauer were rejected (Unfortunately the translation of these two cases studies is not yet available).

In the case of Johann Georg Pöller, both the wife’s evidence proceedings and the maintenance proceedings were broken off in March 1673. In February 1672, Agnes, widowed Braburrin, filed for a separation from bed and board, mainly due to physical violence. The couple had been married since 5 August 1668. As can be seen from the marriage entry, Agnes was the widow of a middle-class fishmonger, while Johann Georg, who came from Bohemia, had been single and had worked as a “servant” until his wedding. He had demanded that Agnes continue to “allow him to trade in herrings” or that she should pay him a provisional annual maintenance of 20 gulden. He justified his request with the fact that Agnes had transferred half of the fish trade to him upon marriage.

Lawsuits for a reduction in maintenance

In the other two cases brought by husbands, the husbands attempted to have the amount of provisional maintenance reduced. In August 1675, Georg Ludwig Gioia, whose occupation is noted in the minutes as “the ruling Roman empress sommelier”, applied for a reduction of the provisional maintenance of 200 gulden, which he had been paying to his wife Margaretha since January of that year. His request was granted, and the maintenance was reduced by half.

In November 1751, Maria Helena Pößlin demanded half of the income of her husband, the “imperial master cook” Johann Georg Pößl, as provisional maintenance during the evidence proceedings for adultery. Instead of the requested half of his income of 600 gulden, the consistorial councils granted her provisional maintenance in the amount of 200 gulden. In June 1752, the secular authorities reduced the amount of the provisional maintenance to 150 gulden. In the hearing on 6 November 1752, the couple negotiated the maintenance again, this time before the Vienna Consistory. Johann Georg demanded a reduction of maintenance or the restitution of things that she had taken from the common household. The consistorial councils rejected the husband’s complaint and confirmed the 150 gulden which the secular authorities had set as provisional maintenance.

Maintenance claims from women

The vast majority of the additional proceedings for provisional maintenance were applied for by women in order to receive maintenance for themselves and any children for the duration of the main proceedings. As already shown in the quantitative results, the consistories usually awarded the women provisional maintenance for the duration of the process, regardless of whether they were plaintiffs or defendants in divorce or separation proceedings. If you put the proceedings for the awarding of provisional maintenance in relation to the place of residence or the responsible consistory, it becomes apparent that it was mainly wives living in Vienna who used the consistory to regulate the provisional maintenance. The under-representation of the Passau consistory is not likely a result of the fact that wives living on the countryside waived provisional maintenance payments. It can be assumed that they chose to bring their maintenance lawsuits to the secular courts because they often lived hundreds of kilometres from the Passau consistory. The latter was, as we explain in the menu item Data Collection, in the capital and residence city of Vienna.

In the qualitative analysis, we want to use some case studies to ask in which situations and contexts spouses turned to the consistory in order to receive provisional maintenance. We are interested in cases where the consistorial councils approved provisional maintenance and where they refused it. And we ask what standards were used to determine maintenance.

From a gender-historical perspective, the few cases in which the wives’ maintenance claims were denied are also particularly interesting. The question of what options the wives had if the mandatory provisional maintenance was not or only partially paid is described in the sub-item “Enforcement proceedings.

Case studies (Unfortunately a translation is not yet available)

What is striking about the case studies which were analyzed in more detail is that the majority of applications were submitted by wives whose husbands had a salary. Even if the married couples were married for only a very short time, the women always knew exactly how much the husbands were paid and usually demanded half for themselves and any children from the marriage. Therefore, the husbands who were sued for provisional maintenance mainly include servants of the Viennese court, the imperial, sovereign and municipal administration as well as members of the military. Although more than 50 percent of the married couples of whom we were able to reconstruct the socio-economic position made their living with a craft, a trade or a trading business, the defendant husbands included only one surgeon, one tailor, one butcher, one goldsmith, one field surgeon, one cattle dealer and one merchant. It is unclear what the law student did for a living. It can therefore be assumed that wives, who usually ran the craft, trade or business with their husbands, negotiated the provisional maintenance in the local secular courts and not at the consistory.

3. Provisional custody

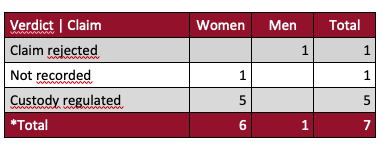

Table 3 | Proceedings for provisional custody (1558-1773)

As Table 3 shows, six of the seven additional proceedings for provisional custody of the children were initiated by the wives. Only in one case – Maria Veronica Scheuringin demanded custody of her son in April 1659 – no verdict was passed due to the applicant’s death. The few surviving case studies draw our attention to the fact that custody proceedings and maintenance were closely intertwined and that the dispute over provisional child custody was based on both material and emotional motives.

Case studies (Unfortunately no translation is available yet)

The few surviving cases show that, with the exception of one case, it was the wives who left the shared home mainly because of domestic violence and who took all or only certain children with them. Not surprisingly, the case studies also show that proceedings on provisional child custody were usually combined with maintenance claims. Depending on the age and sex of the children, disputes involving custody also included concerns about the appropriate upbringing, living conditions and the physical well-being of the children. The same applies to the custody proceedings that were carried out after a verdict in the main proceedings.

Andrea Griesebner and Susanne Hehenberger, February 2021, translation Jennifer Blaak.