1. Follow-up proceedings after tolerance verdict

2. Follow-up proceedings after peaceful cohabitation verdict

3. Tolerance verdicts

4. Case study

1. Follow-up proceedings after tolerance verdict

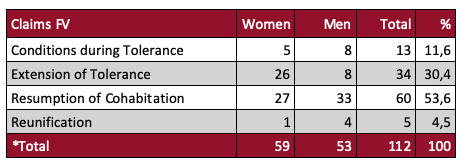

Table 1: follow-up Proceedings after Tolerance Verdict | Women | Men

As Table 1 shows, in the time periods examined 112 proceedings are handed down based on a tolerance verdict. In slightly more than half of these proceedings the plaintiff requested that the court order the husband (in 27 cases) or the wife (in 33 cases) to resume marital cohabitation. While the proceedings involving the request to resume cohabitation were filed by almost an equal amount of wives as husbands, the petitions for the extension of a tolerance verdict were, as can be seen in Table 1, primarily submitted by women (26 females, 8 males).

In 13 proceedings one of the married parties requested that the consistorial court apply conditions to which the husband/wife had to comply for the duration of the tolerance. The concern of the wives was usually to ensure that they received protection from physical or psychological violence. The legal interest of the husbands primarily lay in stipulating conditions regarding the place of residence of the wife for the duration of the tolerance.

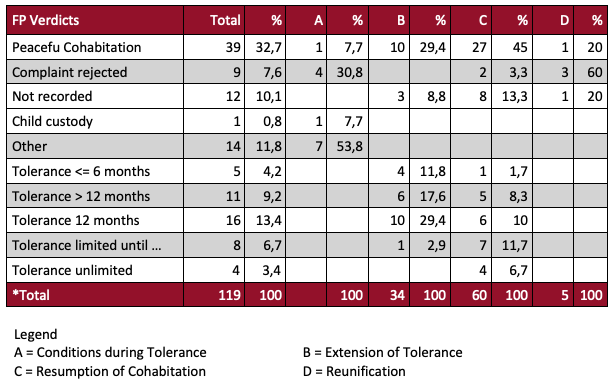

Table 2: Verdict | Legal interest in follow-up Proceedings

Table 2 includes all verdicts in follow up proceedings with the legal interest of A, B, C and D. The slightly higher number of proceedings compared to Table 1 is explained by the fact that table 2 also contains six follow-up proceedings, which did not follow a tolerance verdict in the main proceedings, but a tolerance verdict in a follow-up proceedings. For the complexity of the interlinking of the proceedings, see the case study on the Hadaun*in couple below. As table 2 illustrates, the chances to get an extension of the tolerance were relatively high. In nearly two thirds (21 of 34 cases) of the proceedings petitioning for an extension of the tolerance the consistorial council authorized an extension between six month and 1 year. In one case, the consistory limited the period to the duration of the civil proceedings that the wife’s father was conducting against his son-in-law.

Anton Ebner, a middle-class comb-maker, approached the Vienna Consistory in May 1772. He reported that his wife was neither avoiding the hairdresser Sticker nor living with him [the husband] although the verdict from 8 April 1771 instructed her to sever contact with the hairdresser and to live peacefully with her husband. He reported that her parents had given her “shelter”. At the hearings on 9 May 1772 Josepha Ebnerin did not deny that she was living with her parents. She argued that she had attempted to live peacefully with her husband, but that he had once again “hit and bitten” her, and had slandered her, everywhere referring to her as a whore. Instead of re-asserting a new verdict of cohabitation as the husband had requested, the consistorial councillors authorised a six-month separation from bed and board in Josepha Ebnerin’s favour. After the six-month tolerance period had ended she requested an extension with the explanation that her husband had not “bettered” himself and, in addition to that, was carrying out a legal dispute with her father. At the hearing on 20 November 1772, although Anton Ebner once again insisted upon cohabitation, the consistorial councillors authorised a tolerance verdict which was to stay in effect until the decision was made in the civil process between her husband and her father.

Also more than one third (38.3%) of the proceedings requesting the resumption of cohabitation (23 of 60 cases) the consistorial council did not order the resumption of cohabitation, but rather administered a temporary tolerance, in three cases even an unlimited tolerance, in other words divorced the couple from bed and board.

2. Follow-up proceedings after peaceful cohabitation verdict

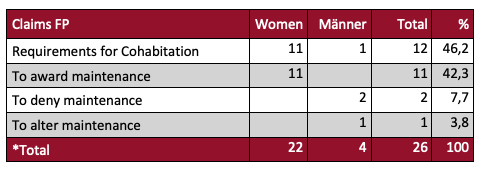

Table 3: Follow-up Proceedings | Verdict | Women | Men

As Table 3 shows these follow-up proceedings didn’t play a statistically relevant role in any of the time periods investigated. But in terms of content they are interesting due to the fact that these proceedings usually involved the settling of the question of whether or not the husbands should have to pay maintenance to the wife or the children no longer living in the same home.

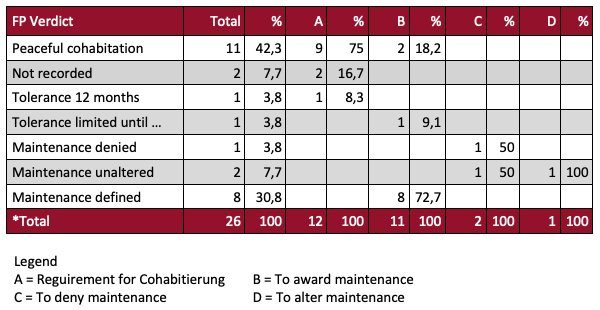

Table 4 Verdict | Legal Interest in Follow-up Proceedings

Table 4 shows that in almost half of these proceedings the Consistorial Council denied the request of the spouse and ordered the married couples to once again live together peacefully.

3. Tolerance Verdicts

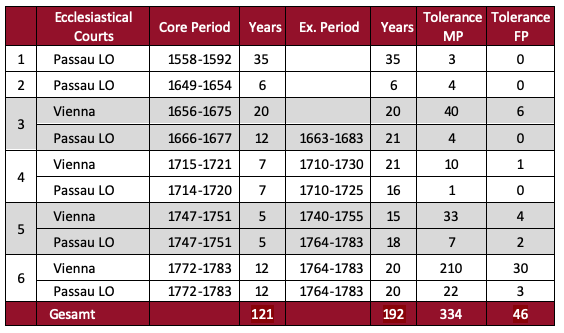

Table 5: Time Periods Examined | Tolerance Verdics

As table 5 illustrates, the consistorial councils granted tolerance in 192 (10.9%) of 1,760 main proceedings and in 46 (32.6%) of 140 follow-up proceedings, i.e. allowed the wife or the husband to life separated from bed and table for a limited or unlimited time period. In the quantitative evaluation of the follow-up proceedings (FV), it should be borne in mind that the tolerance granted in the main proceedings sometimes ended at a point in time which is outside the examined time segments. In this case, any follow up proceedings is no longer part of the sample. Neither can we say how many married couples resumed married life after the period of tolerance had expired. If both parties accepted to no longer share bed and board and the couple have not been reported by the priest there was no need to initiate any follow-up proceedings. These married couples are also hidden from our view.

How complex the chain of proceedings could be can be seen particularly clearly in the case of the matrimonial proceedings carried out by the married couple Magdalena and Adalbert Hadaun*. These proceedings will be analysed below.

4. Case Study: Magdalena Hadaun*in and Adalbert Hadaun (1770–1781)

In May 1771 Magdalena Hadaunin petitioned for a divorce at the Vienna Consistory. Her main argument was that in their almost one year of marriage her husband watched over her with unwarranted jealousy and that he had “abominably” beaten her. The physical violence was confirmed with a doctor’s certificate. In a hearing on 14 June 1771 Adalbert Hadaun objected to the claim of jealousy and legitimized the blows he administered to his wife by stating that his wife had spent the night in a room with two men and had threatened to have him killed. Magdalena objected to these accusations and stated that not two men but her female servant had slept in her room, and that the servant would confirm this. Under the condition that his wife “be put in a place where she would be required to improve her behaviour” Adalbert stated he would consent to a temporary separation and to paying maintenance. The consistorial council granted Magdalena Hadaunin a tolerance of one year.

As the marriage registers from St. Stephan’s verify, the couple was married on 22 July 1770. Magdalena was 26 years old at the time of the marriage and the legitimate daughter of Maria Anna and Bernhard Hofer*in, who made their living as traders of canvas. In regard to Adalbert Hadaun, we know only that he was a widower and that his profession was that of an imperial-royal master wainwright. From the death entry in the registry books of the Viennese parish of St. Karl Borromäus (Wieden/Fourth District), which records his death on 17 November 1787 at the age of 79, we can calculate the he was 60 years at the time of the marriage. He was therefore more than 35 years older than Magdalena. From the baptismal registers of St. Stephan’s (Innere Stadt/First District) we learn that Magdalena was at least his third wife. We were unable to find out when he and Catharina, née Krenin, were married. However, the baptismal records of St. Stephan’s document that the married couple had their daughter, presumably their first child, christened under the name Anna Catharina on 24 July 1738. The married couple had at least five more children whose baptisms are also recorded in the baptismal records of St. Stephan’s. The marriage of their son Ignaz is recorded in the marriage registry of the parish church of St. Stephan’s on 15 June 1783.

After Catharina died Adalbert Hadaun married Katharina, née Spittlin, whose death on 2 July 1766 is reported in the St. Stephan’s death register. Provided that Adalbert did not marry again in the time period between Katharina’s death in 1766 and his marriage to Magdalena in summer of 1770 we can assume that his marriage to the 26 year-old Magdalena was, at least, his third marriage.

In August 1771, not even two months after the Viennese consistorial council had authorized Magdalena Hadaunin to live separated from her husband for one year, she petitioned for the “resumption of cohabitation” and based her petition on the fact that she was pregnant. At the hearing on 7 September 1771 Adalbert Hadaun opposed the petition to resume cohabitation. He argued that it was not he, but rather his wife who had obtained the separation for one year in the first place, and that he could not believe that he was the father of the yet unborn child. The consistorial council decided in his favour and confirmed the tolerance verdict.

On 26 June 1772 the Vienna Consistory once again held a hearings concerning the couple. Magdalena Hadaunin had sued for the resumption of cohabitation since the tolerance period had expired as of 14 June 1772. In addition to this, in the meantime their child had been born. This time Adalbert Hadaun did not even deny being the father of the child, but he still refused to resume cohabitation. He substantiated his refusal with the claim that his wife was leading a licentious life, that she had threatened to kill him, and that such a threat could “easily be carried out […] since he was an old and battered man”. He agreed to pay maintenance to Magdalena and the child. The consistorial council again dismissed the wife’s petition and this time awarded the husband a tolerance period of one year. It is remarkable to note that the wife was not only instructed to behave honourably during the course of this time period, but that she was also told to “refrain from any violence against the defendant”, a formulation which was otherwise used only toward men.

In December 1773 Magdalena Hadaunin petitioned for the resumption of cohabitation for the third time. Her husband once again opposed the petition. The protocol from the hearing on 25 December 1773 records that he stated he would rather die than share bed and board with Magdalena:

"she is an irrepressible devil and it is impossible to live with her, she repeatedly tried to kill me, he would rather kill himself than live with her."

This time the consistorial council did not make a decision already in the summary proceedings, but rather decided upon a conditional verdict in which the husband was sentenced to resume peaceful cohabitation or to initiate evidence proceedings, in which he should present legitimate reasons for not being able to live with Magdalena. As was usual, Magdalena was given the right to counter these claims.

Adalbert Hadaun took up the evidence proceedings for a divorce from bed and board. After almost six months the married couple agreed upon a settlement which was recorded in the consistorial record books on 15 July 1774. Firstly, the husband was required to “meet his wife with respect and to provide her with necessary maintenance and with clothing befitting her social status”, secondly, to pay for her court costs of 110 Gulden within the next 14 days, thirdly, to find new accommodations for the couple and their son by “Jacobi” (25 July), and fourthly, to keep the child with them in their home at least until its third birthday and thereafter to find an appropriate home for it. In return, Magdalena Hadaunin was required to refrain from committing verbal or physical violence against her husband, secondly, not to “go out” without previously informing her husband, thirdly, to avoid all contacts which her husband would deem to be “improper”, fourthly, to meet her husband “peacefully, decently and with the proper amount of loyalty and love”, fifthly, “to be obedient and not to act in opposition to all proper actions” requested [by her husband], sixthly, “not to use insensitive words” when speaking with the children from her husband’s first marriage, and seventhly, to “keep daily accounts of all of the money which she received from him for the housekeeping”.

The settlement was kept for only a few months. At the beginning of 1775 the husband filed for a divorce from bed and board. In the hearing from 24 March 1775 he stated that his wife was not honouring the regulations stipulated in the settlement, that she was “quarrelling, fighting and hitting” him on a daily basis, and that he, as an “old, enfeebled man” could not put up resistance, and that he could not be sure that his life was not in danger. As evidence for the physical violence against him he submitted three doctor’s certificates and provided witness statements. The physical violence attested to in the latter had resulted in her being placed under arrest for three days on orders from the local court.

Magdalena Hadaunin did not deny the accusation of “fighting”, however she countered that not she, but rather her husband, had started these fights, and also submitted evidence in the form of a certificate stating that her husband “had brutally beaten her”. According to Magdalena she had nothing against her husband’s request for divorce, especially „since he was not keeping up with his conjugal duties anyway“, in other words he was not sleeping with her. Magdalena however insisted upon her husband being required to pay maintenance.

The consistorial council once again passed a conditional verdict in which the husband was required “to prove the blows and cruelty, as required, for a divorce from bed and board.” Magdalena was once again given the opportunity to present counter evidence. For the duration of the evidence proceedings the council allowed the married couple to live separated from bed and board and threatened both of the married parties with arrest if one or the other should commit physical or verbal violence against the other.

On 17 January 1777, after evidence proceedings lasting almost two years, the consistorial councillors ruled that

"there a not enough reasons to warrant a divorce, but enough reasons for granting a longer tolerance period."

The verdict authorised a two year separation from bed and board instead of the divorce which the husband had petitioned for. The court stipulated that 12 Kreuzer per day were to be as maintenance for both Magdalena and the child, whereby the court records noted that the plaintiff was paying this maintenance out of “goodwill”. The verdict also included the statement that Magdalena would lose her right to maintenance if she publicly insult her husband or his children from his first marriage.

In January 1779, after the two year tolerance was over, Magdalena submitted a fourth request for the resumption of cohabitation which she justified this time with the claim that her husband did not voluntarily pay the maintenance which he had promised to pay and that she always had to force its execution. Adalbert Hadaun continued to oppose cohabitation with the explanation that “the hate and bitterness” had not ended and that already two years ago he

"could have been granted a divorce on the grounds of cruelty, if he had not, to save himself further proceedings, voluntarily agreed to a tolerance and the payment of maintenance."

Adalbert Hadaun declared to be willing to continue to pay maintenance to his wife and child. The consistorial council decided in his favour in that they extended the tolerance period with the conditions from 1777 for another two years.

After this tolerance period ended Magdalena petitioned for the resumption of cohabitation for the fifth time, this time with the argument that no legitimate reason for an extension of the tolerance existed. At the hearing on 19 March 1781 Adalbert Hadaun once again made mention of his advanced age which necessitates a peaceful and quiet life, and requested that the tolerance once again be extended. The consistorial council once again decided in his favour and extended the tolerance for yet another two years.

After this entry there are no more traces of this married couple in the consistorial records. There are also no references to this couple in the divorce dossiers we investigated from the Viennese Civil Magistrate’s Office, which, as of November 1783, was responsible for the divorces of couples living in Vienna. Starting from the death record of Adalbert Hadaun, which, as was mentioned above, had been documented in the death records of the parish of St. Karl Borromäus in Vienna, the Viennese Civil Magistrate would have been responsible.

Although it cannot be ruled out that the records are simply no longer available it is very unlikely that Adalbert Hadaun petitioned for a divorce after 1783. For the first three years of its existence the Marriage Patent, which came into effect on 1 November 1783, authorised only “uncontested divorces”, and it is not to be expected that Magdalena would have been willing to agree to an uncontested divorce. But also the options which Magdalena Hadaunin had at her disposal were restricted by the change in legislation. Apart from contested divorces the civil courts could not accept any petitions for the “order of cohabitation” in the first years of their jurisdiction, but had to refer the disputing parties to the police.

Seen in the light of all of the cases examined, the delineated case of the married couple, Magdalena and Adalbert Hadaun*in provides an interestingly exceptional case which allows for the exploration of the possibilities for the use of the consistorial courts. It appears as if the situation that spouses refused to resume married life after a tolerance, even if the tolerance was limited to a few months or years, was the rule rather than the exception.

Andrea Griesebner, 2018, translation Jennifer Blaak

Last update: December 2020