1. Consistory of the Diocese of Vienna

2. Consistory of the Lower Offizialat of the Diocese of Passau

The ecclesiastical courts within the realm of our investigation, which are now referred to as diocesan courts, used to be called consistories. Each bishopric and each diocese respectively had, and still has, its own ecclesiastical court which was ruled by the Official or the Vicar General.

The church courts decided, for example, over whether or not the wedding vows were valid or if a person who had been sued for not honouring a promise of marriage would be allowed to marry another person. They granted or refused marriage dispensations for persons, who on the basis of their degree of blood relations, denominational differences or previous acts of adultery, according to the rules of canon law were not allowed to remarry. In addition to this, they also decided whether or not a marriage could be annulled or declared null and void, and they allowed or refused married people the right to live in separate households.

Since the middle of the 18th century the consistories had to employ the services of a Defensor Matrimonii, a Defender of the marriage Bond in all annulment proceedings. The office of Defensor Matrimonii was introduced by Pope Benedict XIV in the Papal Bull referred to as the Constitution Deimiseratione from November 3, 1741 in order to impede the process of annulment.

1. VIENNA CONSISTORY

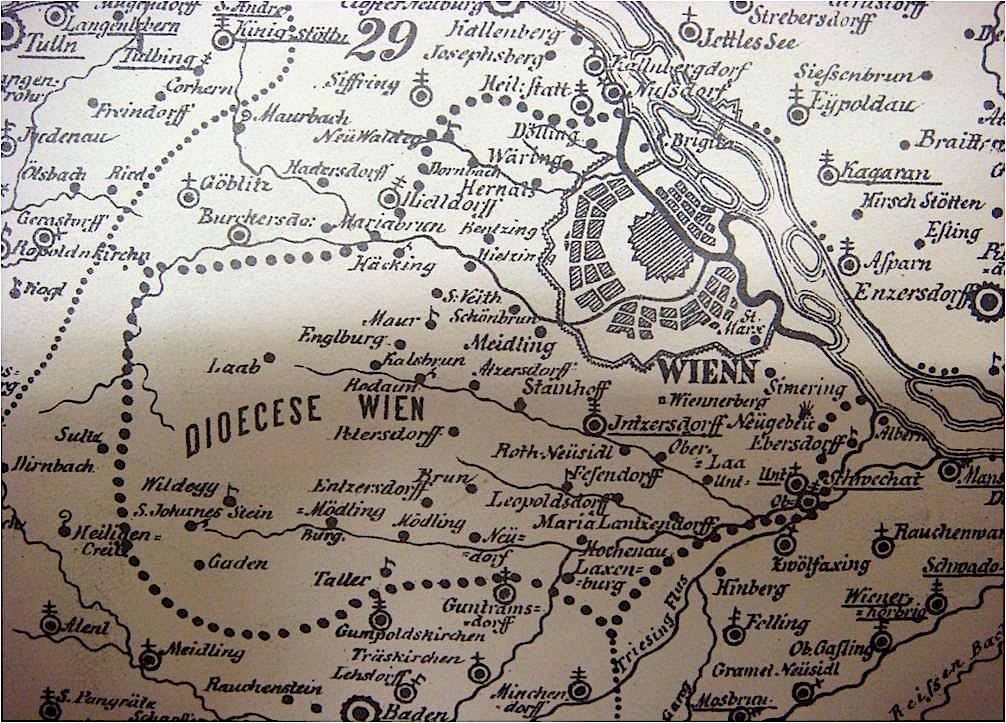

The Viennese consistory located in the Wollzeile, in what is now known as the First District, was responsible for married couples residing in the (arch)diocese of Vienna. Until 1729 the diocese’s, and as of 1722 the archdiocese’s, area of jurisdiction was limited to the inner city of Vienna, its suburbs, its periphery, and a few neighbouring villages and markets in the surrounding area. The border between the Lower Officialat of the diocese of Passau and the archdiocese of Vienna was altered in 1729, when the diocese of Passau had to cede the greater part of its parishes in the Quarter Below the Vienna Forest (Viertel unter dem Wienerwald, now the “Industry Quarter”), to the archdiocese of Vienna.

Joseph Haas, Tabula Geographica totius dioecesis Pataviensis in decanatus divisa et jussu Celsissimi ac Reverendisimi Domini Domini Josephi Dominici S.R.J. Principis et Episcopi Patav. Comitis de Lamberg in lucem data 1723. Diözesanarchiv Wien, Foto: Bildausschnitt: Diözese Wien, Andrea Griesebner.

2. PASSAU CONSISTORY OF THE LOWER OFFICIALAT

The Diocese of Passau was divided into two administrative units already in the 14th century. The eastern part of the diocese was administered by its own official who carried out all of the usual episcopal functions, including that of legal jurisdiction. Many of the parishes in the Archduchy of Austria below the Enns – from the Ybbs River in the west to the Piesting River in the south – belonged to the eastern part of the Diocese of Passau, referred to as the Lower Officialat.

Joseph Haas, Tabula Geographica totius dioecesis Pataviensis in decanatus divisa et jussu Celsissimi ac Reverendisimi Domini Domini Josephi Dominici S.R.J. Principis et Episcopi Patav. Comitis de Lamberg in lucem data 1723. Digitalisat: Archiv des Bistums Passau. Line to mark the border: Andrea Griesebner

Up until the church reforms of Joseph II the Official presides over the Passau consistory in Vienna, located in the Passauer Hof bei unserer lieben Frauen auf der Stiegen (now ‘Maria am Gestade’). The Passau Consistory of the Lower Officialat had marriage jurisdiction for all married couples whose residential parish belonged to the Lower Officialat of the Diocese of Passau.

USE OF COURTS

In many divorce proceedings the married couples were not standing in front of the court for the first time. Either one party had already appealed for an order for the cohabitation of a partner living by her- or himself, or had used the consistory to negotiate the conditions of cohabitation. Rejected claims were usually followed by renewed litigation.

Also married couples who, with consistorial approval, were allowed to live separated from bed board, typically for one to three years, were frequently mentioned in the consistorial protocol books after the ‘tolerance’ was over: be it because one party appealed for the cohabitation to be resumed, or the opposing party submitted an application asking for an extension of the time of ‘tolerance’.

The consistory sometimes – even in the case of temporary separations – determined the consequences of the separation, such as maintenance settlements, division of the property or custody of children, in additional proceedings.

If one of the married parties did not adhere to the judgement the consistory was also used for execution proceedings to enforce the judgement.

Andrea Griesebner 2016, translation Jennifer Blaak

Last update: Andrea Griesebner, December 2020.