1. Source Survey

2. Quantitative Results

1. Source Survey

As described in the menu item marriage proceedings, we were able to identify a total of 670 married couples in the examined time segments of the period from 1783 to 1850, who negotiated their disputed divorce in 697 proceedings before the Vienna Civil Magistrate (57%), requested the approval of an uncontested divorce A (32.6%) or an uncontested divorce B (7.2%), sued their separated spouses for cohabitation (2.6%) or demanded the annulment of the marriage (0.6%) or the reunification after a divorce (0.1%).

What do we know about these 670 wives and husbands? Similar to our efforts for the early modern married couples, we have systematically augmented the information obtained from documents from the proceedings with additional personal data. Once again, we used mainly the marriage, baptism and death registers of the parishes, which are available as digital copies on Matricula Online. This research was somewhat easier for the modern married couples, since we were able to reconstruct the places of residence of the married couples in part through the priest´s certificates, which were attached to both contested and uncontested divorce petitions and were partly archived together with the other documents.

Priest’s Certificate

As a rule, the parish priest of the place of residence issued the priest’s certificate. This included the following information in the case of contested divorces, as the following example shows:

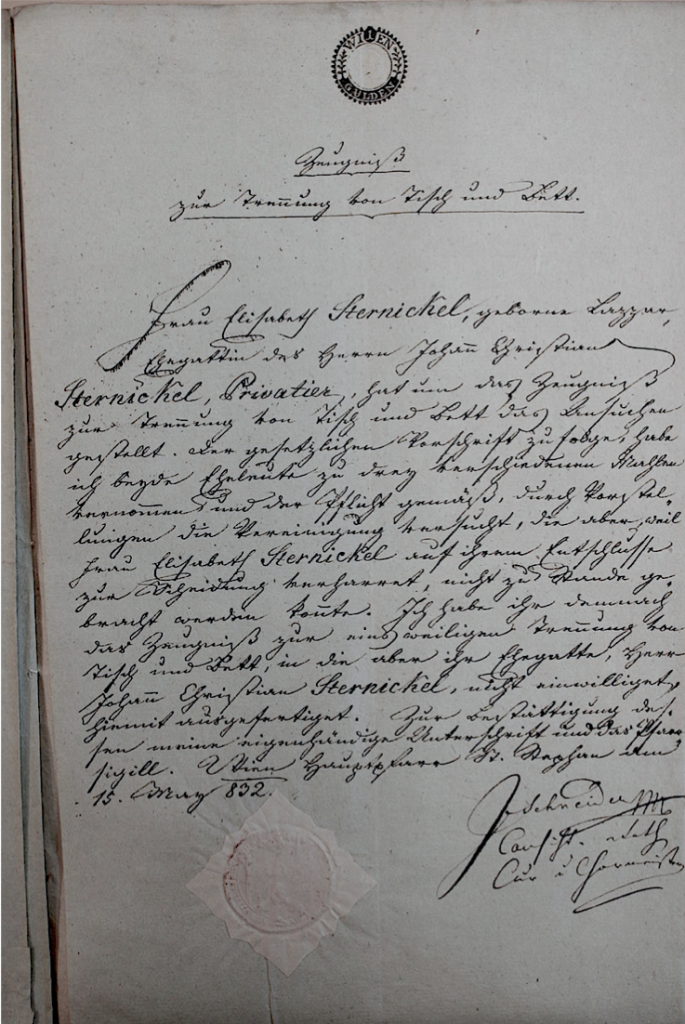

Digital Copy: Separation certificate of Johann Christian and Elisabeth Sternickel dated 15 May 1832.

By way of introduction, the priest explained which spouse had requested a divorce, separation or dissociation of bed and board (the three terms were used synonymously). He then recorded that he had tried to reconcile the couple on three separate dates, but that these attempts at reconciliation had been unsuccessful. Usually it is also mentioned which spouse resisted reconciliation. In the priest’s testimony above, for example, it states that “Mrs. Elisabeth Sternickel persists in her decision to divorce.” The priest’s certificate was dated and signed by the priest himself. Some, but not all, priest’s certificates are marked with a location and the parish seal. In the example above, we have the information that the priest’s certificate was issued on 15 May 1832 in the main parish of St. Stephan in Vienna by consistorial councillor J. Schneider, curate and choir master. If the priest’s certificate contained only the name of the parish priest, we used his name to research the parish. For Roman Catholic couples, we mainly used the following reference works: Hof- und Staatsschematismus des österreichischen Kaiserthums (Court and State Schematism of the Austrian Empire) (1807), Verzeichniß über den Personal-Stand der Säkular- und Regulargeistlichkeit der erzbischöflichen Wienerdiözes (Directory of the Personnel of the Secular and Regular Clergy of the Archdiocesan Diocese of Vienna) (1815) as well as the Personal-Stand der Säcular- und Regular-Geistlichkeit der erzbischöflichen Wiener Diözese (Personal Status of the Secular and Regular Clergy of the Archdiocese of Vienna)(1829 to 1857), which are available online via Google Books.

Since the priest’s certificate had often not been archived in the case of uncontested divorces, we researched additional personal data on the modern married couples also using the online portal GenTeam, through which we found especially references to the marriage registers. This research was a challenge for approximately 20 percent of the married couples with a very common last name, such as Adler, Bauer, Mayer or Weber. If the search for the marriage registers on GenTeam was unsuccessful, we systematically worked through the indices of the marriage parish which we suspected to be applicable according to information from the divorce files. If this search also remained without results, we also searched those Viennese parishes on Matricula Online for which indices were not yet available on GenTeam. Here, too, we were unable to take some marriage registers into account, because they had not yet been digitised or activated on matricula at the time at which we were doing our research.

Compared to the early modern period, the entries in the marriage registers are usually more extensive and are listed in categories. For unmarried persons, the name and place of residence of the parents and the occupation of the father are usually recorded, and rarely also the mother’s occupation. In addition, we usually learn the place of residence of the bride and groom, their occupation, their age and their marital status. Another new feature, as the two screenshots below show, is that the forms of the marriage registers now differentiate the religion to be entered in two categories: Catholic and Protestant.

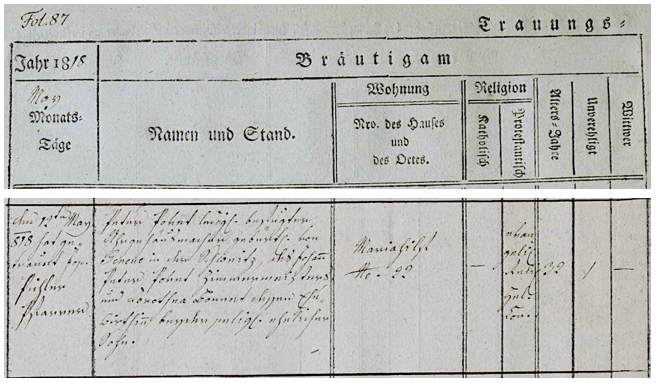

Screenshot: Entry on groom Peter Bovet in the marriage register of St. Josef ob der Laimgrube 1814–1820, fol. 87

As the screenshot of Peter Bovet’s wedding entry shows, the priest in this case had specified the religious confession: “Protestant religion, hel[vetic] con[fession]”. In other entries, the priests used the abbreviations AB (Augsburger Bekenntnis) or AC (Augsburg Confession) or Reformed or HC (Helvetic Confession). Based on the methodological consideration that priests used handwritten additions primarily for the exceptions, we assigned entries without further specification to the Lutheran denomination. The denominational affiliation could be clearly determined in those cases where the couple had married in the Lutheran or in the Reformed city church.

In the screenshot above, we also learn that the groom Peter Bovet was 32 years old and single at the time of the wedding, and that he was a watch case maker, lived at Mariahilf No. 22 and was originally from Geneva, Switzerland.

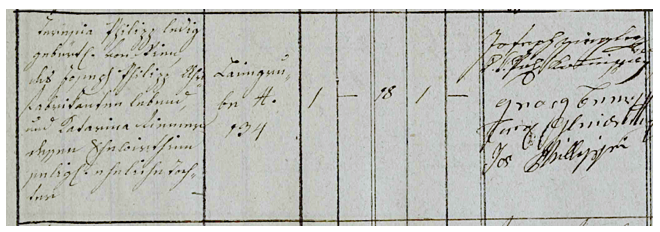

Screenshot: Entry on bride Theresia Philippe in the marriage register St. Josef ob der Laimgrube 1814–1820, fol. 87.

The bride, Theresia Philippe, was 18 years old, unmarried and Catholic at the time of the wedding. She was the daughter of a watch manufacturer and lived at Laimgruben No. 134. We don’t know if she had completed an apprenticeship or was employed at the time of the wedding. If the bride was widowed, the marriage register still usually contains only the name and occupation of the deceased husband. If, in contrast, the bridegroom was widowed, the name of the deceased wife was still rarely entered in the registers of the 19th century.

From the age given at marriage, we calculated the year of birth of the bride and groom. Like the early modern married couples, the age calculated in this way should be interpreted with caution. As becomes clear in comparison with some researched baptism registers, the ages given are still far from being exact dates, even in the 19th century.

To complete the personal data, in a final step we also searched for the spouses’ dates of death. For this research, we were able to rely primarily on the online newspaper archive of the Austrian National Library ANNO (AustriaN Newspapers Online) – in addition to the search via GenTeam and Matricula Online. Based on the obituaries in the full-text searchable issues of the Wiener Zeitung (Vienna News), we were able to find out the date and place of death for some persons.

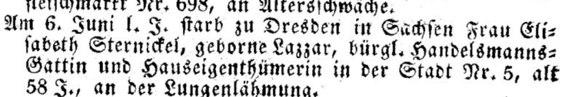

Screenshot: Obituary of Elisabeth Sternickel in the Wiener Zeitung (Vienna News) of 3 July 1849, p. 9

From the obituary in the Wiener Zeitung (Vienna News) we learned that Elisabeth Sternickel had moved to Dresden and died there in 1849 at the age of 58. However, we don’t know when she moved to Dresden. What is certain is that in June 1832 she sued for a contested divorce and justified it not only with physical violence, but also with poor economic management and the dissolute lifestyle of her husband. At the end of July 1832, the couple agreed on a divorce settlement (see also the case description under the menu item custody).

This information in turn often enabled us to research entries in the parish death registers, which, in addition to age and cause of death, often also provided information about social status and place of residence at the time of death.

Couple’s Place(s) of Residence and Responsible Priest

If the couple had different places of residence at the time of the marriage proceedings, we determined their common place of residence during the marriage as follows: If the husband‘s residential address was in the parish that had issued the priest’s certificate to the couple, we entered the husband’s residential address in the database as the couple’s last common place of residence. This decision is based on the consideration that from 1786 the husband was entitled to determine the joint place of residence and the wife was obliged to follow the husband to his place of residence (cf. The explanations on the menu item norms). If the husband’s place of residence did not match the location of the priest’s certificate’s, but the wife’s place of residence was in the corresponding parish, we assumed the wife’s address to be the couple’s place of residence. In this case, it could be assumed that the wife had remained in the shared apartment, and the husband had moved out, which was the case with the Sternickel couple in around 1832, as the house in the centre of Vienna belonged to Elisabeth Sternickel.

One exception to this were married couples, of which one of the spouses was in prison. In 1831, for example, the Viennese magistrate requested permission to send a judicial commission to the Imperial and Royal Provincial Penitentiary to divorce Franz and Barbara Walser. Before that, according to the judge, the mandatory attempts at reconciliation would still have to be completed by the responsible priest and the wife, who was petitioning for divorce, at the prison with the former hired coachman, who had been sentenced to several years in prison. However, the Lower Austrian state government rejected this request, since “convicts […] sentenced to jail […] can neither conclude a binding contract, nor establish a last will […]” with those living outside.

The other exception was couples of Mosaic religion or non-Catholic denominations. The couple Karl August and Christiane Zettler, both Lutheran AB, living at Gumpendorf No. 49 at the time of the divorce proceedings, presented the testimony of the superintendent and preaching pastor Johann Johann Wächter from the Lutheran city church in 1816. If a Catholic wife wanted to obtain a divorce from her Lutheran husband, the Catholic priest’s certificate weas usually sufficient, as in the case of Theresia Roth in 1831 or Josepha Mathes in 1848. Occasionally mixed-denominational married couples presented two different priest’s certificates, as was the case with Philipp Christian and Anna Mack in 1830 or the above mentioned Elisabeth Anna and Johann Christian Sternickel, who in 1832 also presented a Protestant certificate in addition to the Catholic separation certificate mentioned at the beginning.

Digital Copy: Certificate for Johann Christian and Elisabeth Sternickel from 11 April 1832

In contrast to the Catholic priest’s certificate cited above and issued five weeks later, the Lutheran preaching pastor recorded on 11 April 1832, that although he had wanted to carry out the three prescribed attempts at reconciliation, Johann Christian Sternickel had refused to appear at the second and third appointments “since a judicial divorce was neither sought nor intended on his part”. He could only confirm that Elisabeth Sternickel had come to all three appointments and “always insisted on her intention to be separated”.

2. Quantitative Results

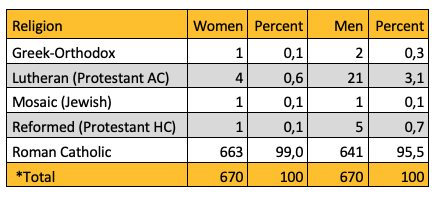

RELIGION

As the tables below display, the vast majority of the 670 married couples belonged to the Roman Catholic Church. It is noteworthy that as many as 32 married couples were interdenominational, whereby it was conspicuously more often the husband who did not belong to the Roman Catholic denomination. It is also striking that almost all individuals who did not belong to the Roman Catholic denomination were not born in the Archduchy, but rather in other parts of the monarchy, in other territories of the Empire or in Switzerland.

Table 1 a and 1 b: Religion of spouses

Interdenominational married couples

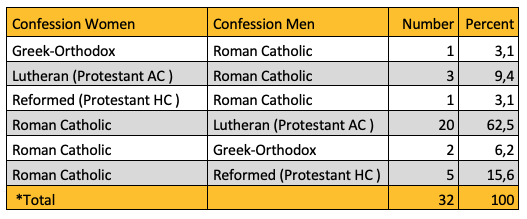

DATE OF MARRIAGE

While we were often unable to reconstruct the date of marriage for early modern couples, the date of marriage was often requested at the hearing in secular courts in the case of contested divorces. The date of marriage often remained unmentioned in the applications for approval of uncontested divorce, where we were also referred to the parish registers. As the table below shows, we were able to determine the marriage date for three quarters of the 670 married couples who had marriage proceedings before the civil magistrate in the time segments examined.

Table 2: Study Period | Marriage Date

MARITAL STATUS | WEDDING

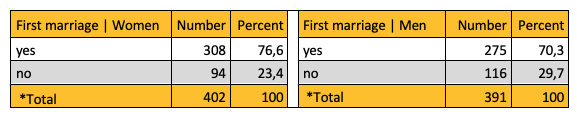

As the table below shows, we were able to determine the marital status of 402 wives and 391 husbands at the time of their marriage from the entries in the marriage registers.

Table 3: Marital status at the wedding by gender

At first glance, the difference to early modern married couples is striking. While in the early modern period it was at least the second marriage for a slight majority of both the women and the men, in this period just over three quarters of women and slightly more than 70% of the men had never been married before.

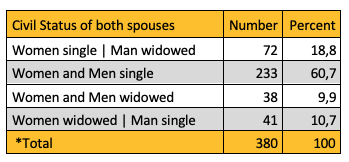

As the next table shows, we were able to clearly determine the marital status of both spouses in 384 married couples. Here, too, there is a clear difference to the early modern married couples. While in the early modern era only just under a third of the brides and grooms had never been married before, the portion of modern married couples where both the bride and the groom had not previously been married is almost 61%. The second most common constellation was a widower marrying a woman who had never been married before (18.8%). In third place (10.7%) there was the combination of a widow who chose to marry a usually considerably younger bachelor. At 9.9 percent, the constellation of a widowed woman marrying a widowed man was statistically the least common constellation.

Table 4: Marital status at the wedding by married couple

MARRIAGE AGE

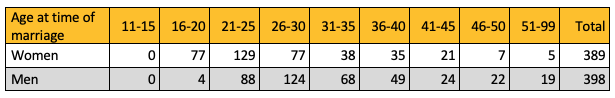

We were able to find out the age of marriage for 389 women and 398 men. Here, too, there is a clear difference to the early modern married couples. The fact that modern married couples were on average younger when they got married reflects the fact that at this time the proportion of those getting married for the first time was significantly higher. One fifth of the women (77) but only one percent of the men (4) were under the age of 21 at the wedding. With 5 women and 19 men, the proportion of marriages, where at least one spouse was already older than 50 at the time of the wedding is astonishingly high. As the table below also shows, the largest group of women is found in the age cohort between 21 and 25 years (33,2%), while the largest male cohort is the age group from 26 to 30 (31,2%).

Table 5: Age at time of marriage by gender

AGE DIFFERENCE IN MARRIED COUPLES

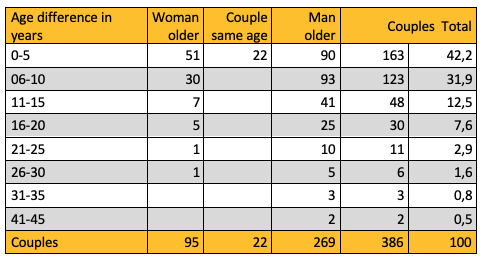

For 386 of the modern married couples, we were able to find out the ages for both the husband and the wife: As shown in the table below, 22 of the married couples had no age difference between the husband and wife. Just over two-fifths of the married couples (42,2%) were close to the same age, with an age difference of up to 5 years. Another 31,9% of the married couples had an age difference between 6 and 10 years, with the husband being older in three-quarters of the cases. In an overwhelming majority of the cases where there was an age difference of more than 11 years, it is the husband who was the older spouse. Among the 22 married couples with an age difference of more than 21 years there are only 2 married couples where the woman is older than the husband, among the five married couples with an age difference of more than 31 years, it is always the husband who is the older spouse. In other words. Only two women in the source sample chose a husband who was more than 20 years younger, while conversely 20 men chose women who were more than 20 years younger.

Table 6: Age difference between spouses

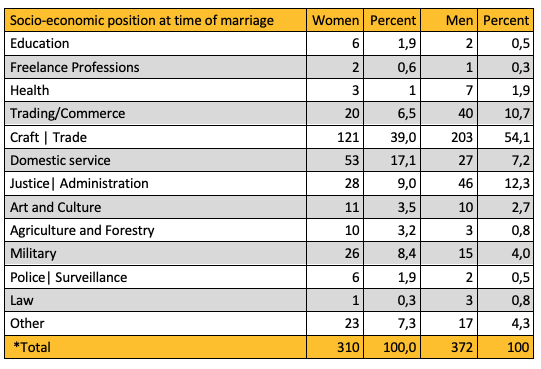

SOCIAL STATUS AT TIME OF MARRIAGE

For 310 women (46.3 %) and 372 men (55.5 %) of the 670 married couples, we were able to make a rough social classification. As already stated in the description of early modern couples, the assignment made to one of the economic sectors listed in the table below must be interpreted with caution. For one thing, it was difficult to define economic sectors that transcended space and time because of the long period of investigation, from the mid-16th to the mid-19th century. On the other hand, it should be borne in mind that even if the entries in the marriage registers of the 19th century are usually more detailed, they still obey a patriarchal logic. We seldom find out how previously unmarried and widowed women made their living in the time before the wedding. This is also the case in the screenshot of Theresia Philippe’s wedding entry from 1832 which is shown above. If we had no other information, we assigned unmarried women and men to the economic sectors of their parents and widowed women to the economic sectors of their deceased husbands during this examination period as well.

Table 7: Socio-economic position at marriage by gender

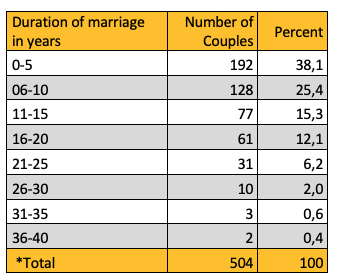

DURATION OF MARRIAGE

If we relate the marriage to the date of the first lawsuit or petition for an uncontested divorce, we see yet another a difference from early modern couples. While in the early modern period half of the married couples had marital conflicts which were so severe already in the first five years of marriage that they left traces in the protocol books of the two consistories examined, this proportion is only 38.1% for the modern married couples. When making this comparison, however, it is important to keep in mind that in this period of investigation, cohabitation lawsuits accounted for only 2.6 percent of the proceedings, whereas in the early modern period, together with the lawsuits negotiating the conditions of marital cohabitation, they accounted for 26.5 percent. At one quarter, the proportion of married couples who filed for divorce after 6 to 10 years of marriage is approximately as high as it was in the early modern period. At 7.8 percent, the proportion of modern couples who had been married for more than 21 years at the time of the first proceedings before the civil magistrate is also comparably high, and 5 couples (1%) had even been married for more than 30 years.

Table 8: Duration of marriage before first marriage proceedings

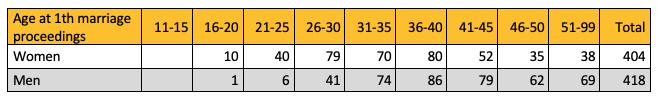

AGE AT TIME OF DIVORCE PETITION OR LAWSUIT

For 404 women and 418 men, we were able to reconstruct the age at the time of applying for an uncontested divorce or at first filing a lawsuit for divorce, annulment, or cohabitation. This slightly larger amount of data compared to the data on the age at marriage, is once again due to the fact that we could not determine the marriage date for all married couples. As the table below shows, 10 women but only one man were under 20 years of age at the time. 36 Women and 67 men were already over the age of fifty.

Table 9: Age at first marriage proceedings by gender

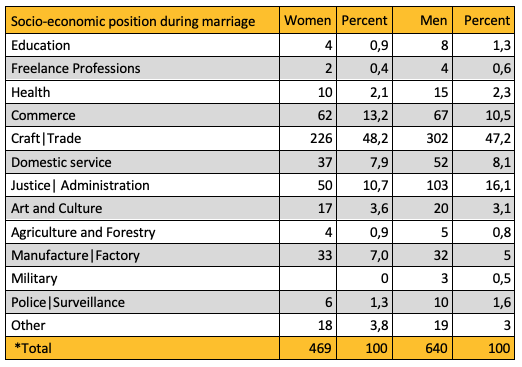

SOCIAL STATUS DURING MARRIAGE

The following two tables provide an insight into how the wives and husbands earned their living during the marriage. In the case of uncontested divorces, we generally included the occupational information from the applications for divorce approval; in the case of contested divorces, which could last for years, we mainly included occupational information that related to the time being married in the personal database. The socio-economic positioning of the wives was made more difficult by the patriarchal logic of their positioning via the parents or husbands, which in the 19th century was no longer used in only in the parish registers, but also in the files from the proceedings. While in the consistorial minutes of the early modern period women who practiced a craft or a trade together with their husbands were listed as master tailors, tradeswomen, or master bakers, in the 19th century they appear only as spouses, to whom the record keepers added the husband’s profession. Sticking with the example above: The wives are referred to as the master tailor’s wife, tradesman’s wife or master baker’s wife. Since it becomes clear in the microstudies that wives and husbands as a rule also formed work couples in the 19th century, we assigned wives to the husbands’ occupational sectors. Excepted from this, of course, were all those cases where the husbands had an independent profession as civil servants, which meant that we were generally less able to obtain professional information about the wives.

Table 10: Socio-economic status of the spouses by gender

If we take a closer look at the craft and trade sector, which was the most strongly represented with almost half of the wives and husbands, it becomes apparent that, similar to the early modern era, the cloth-producing and textile- and leather-processing sectors accounted for the largest share, followed by the construction, wood and metal crafts with more than a fifth of wives and husbands. Innkeepers and men and women who worked in food and beverage production were also strongly represented among the divorcing spouses. The fact that the proportions of women and men do not differ significantly across sectors is due, at least in part, to the method of occupational identification and socio-economic positioning described above.

Table 11: Craft and trade of spouses by gender

PLACE OF RESIDENCE DURING MARRIAGE

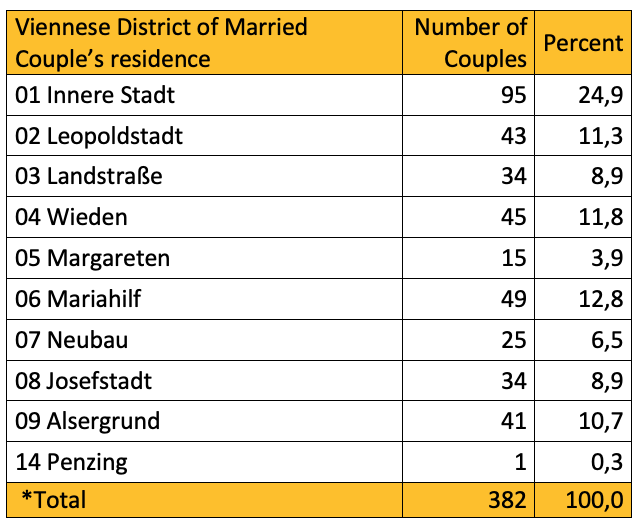

For 382 of the 670 married couples (57%), we were able to determine the couple’s place of residence. As the table below shows, the couples who had their marriage proceedings before the civil magistrate of the City of Vienna lived in the Inner City or within the suburbs located between the Glacis and the Linienwall, today’s districts 1 to 9. The only exception, where the couple had lived in Penzing, can be explained by the fact that the husband, Johann Petrasch, lived in Josefstadt (8th district) at the time of the uncontested divorce proceedings in 1812, and the husband’s place of residence also determined the competent court. The fact that a quarter of the married couples had their residence in the Inner City should be seen against the background that more people also lived in the Inner City than in the suburbs.

Table 12: Married couple’s place of residence

Literature Used

In a first quantitative evaluation, we looked at 396 married couples who were involved in disputed marriage proceedings before the civil magistrate of the City of Vienna. The research on these couples is financially supported by the Department of Culture of the City of Vienna. For these first results, see: Birgit Dober, Andrea Griesebner, Susanne Hehenberger and Isabella Planer, Strittige Scheidungen vor dem Wiener Zivilmagistrat (1786–1850). A project report in: Frühneuzeit-Info 30th year/ 2019, 188-195.

Andrea Griesebner, Susanne Hehenberger, November 2020, translation Jennifer Blaak

last update: Andrea Griesebner, February 2022.