1. Conditional final verdict

2. Initiation of evidence proceedings

3. Verdicts after evidence proceedings

1. Conditional final verdict

As described under the sub-item norms, judges could either decide upon the claims for annulment or contested divorce already in the summary proceedings or order one or both spouses to prove their accusations in a further procedural step, called evidence proceedings. In contrast to the early modern period, the conditional final verdict, often referred to in the sources as an “evidence verdict”, did not prescribe the verdict which would come into force if “lost”, but rather defined the verdict that would come into effect if the “witness presenter” succeeded in producing the required evidence. In the sources examined, conditional final judgments have been handed down only from the Magistrate of Vienna and not from the other magistrates or local courts

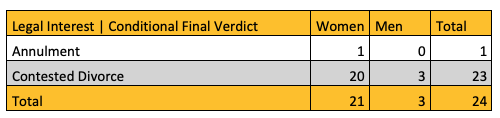

Table 1: Legal Interest | Conditional Final Verdict | Gender

At first glance, the evidence proceedings played a minor role in quantitative terms. As Table 1 makes clear, the judges of the Viennese Magistrate rendered a conditional final verdict in only one out of four and in 23 out of 397 (see table 3) contested divorce litigations for evidence proceedings. In total, 21 women and three men were thus given the right to provide evidence for the alleged misconduct in this further procedural step.

In four cases, we found no indication in the surviving files that the wives or husbands initiated evidence proceedings. In the case of the couple Konstantia and Jakob Santner, which we briefly mentioned in the sub-menu norms, no evidence proceedings are documented. In the conditional verdict from 6 September 1810, the judge ordered Konstantia Sandner to prove the alleged physical violence of her husband with witnesses and an oath. Presumably, Konstantia Sander did not initiate the costly evidence proceedings. We do not know if the couple once again lived together. What is certain, however, is that the husband filed for an uncontested divorce B (see methods) five years later and that the couple reached a divorce settlement on 21 October 1816, in which Konstantia waived all maintenance payments from her husband.

2. Initiation of evidence proceedings

Table 2: Legal Interest in Evidence Proceedings | Gender

As can be seen in Table 2, 18 women and 2 men initiated evidence proceedings. In one proceeding, the wife attempted to have the marriage annulled. The conditional final verdict of 5 July 1784 ordered Katharina Hakl

“to prove that the alleged inability of her husband to father children had already existed before the contracting of the marriage bond, and that his ability could not be restored.”

What is remarkable about this conditional final judgment is that Katharina Hakl was not supposed to prove the husband’s impotence, as usual, but the husband’s inability to procreate. I will come back to this case below. The other proceedings were aimed at divorcing the marriage from bed and board. With the exception of one proceeding, the conditional final judgment ordered the wives and both husbands to prove the physical violence, in some cases also the excessive consumption of alcohol and the neglect of the economy (this can mean the household as well as the trade or craft) by means of witnesses and by swearing the so-called main oath (“Haupteid”).

According to the conditional final judgment of 29 December 1806, Anna Marker had to prove that she could not have conjugal sexual intercourse due to illness. Unfortunately, her complaint has not been handed down, but her argumentation can be reconstructed from the statement of the judge, who agreed to the divorce on the condition:

“that the plaintiff is able to prove through evidence offered by experts that the illness of Anna Marker, who is a m(inor), makes conjugal sexual intercourse impossible, and only as long as the illness does not cease” (WStLA 1.2.3.2.A6 Sch. 5, 34/1806).

As can be seen from the quotation, Anna was a minor at the time of the lawsuit and was therefore represented by a curator, who is also referred to as the plaintiff in the quote above. The 22-year-old daughter of a municipal construction worker and the 36-year-old blacksmith from Silesia got married in the Viennese parish church of the Schotten on 30 April 1804. Anna Marker and her curator appealed against the conditional final judgment. The Imperial Royal Court of Appeal upheld the conditional final judgment of the magistrate and ruled on 12 May 1807 that the divorce from bed and board would be approved on the condition:

“that the plaintiff is able to prove by means of evidence offered by experts that the continuation of the sexual intercourse would endanger the health of the plaintiff, convalescent patient Anna Marker, or would be associated with particular hardship for her.”

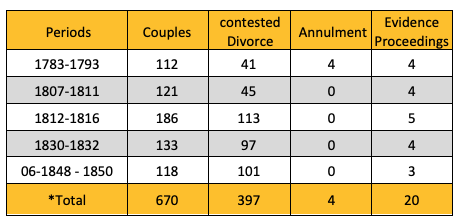

Table 3 – Periods | Contested Divorce Claims | Evidence Proceedings

Table 3 correlates the 20 evidence proceedings with the examined time segments and clearly shows that the evidence proceedings are distributed over all examined time segments. The four proceedings aimed to annul the marriage are limited to the first time segment. The background to this, as we explain in the sub-item norms, is that the Vienna civil magistrate could decide on the annulment of marriages only in the first two years of its jurisdiction.

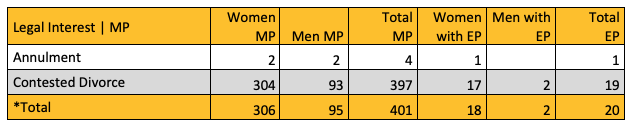

Table 4: Legal Interest at MP and at Evidence Proceedings | Gender

Table 4 lists all contested complaints in relation to the gender of the plaintiff spouse. The first three columns list the number of main proceedings (annulment or uncontested divorce), the next three columns list the number of proceedings in which a spouse initiated evidence proceedings. It becomes clear that 90% of the evidence proceedings were conducted by women, although only three quarters (76.3%) of the contested proceedings were initiated by them. The fact that evidence proceedings played a significant role in the contested lawsuits becomes clear when we consider that many of these proceedings for contested divorces were settled by means of a divorce settlement.

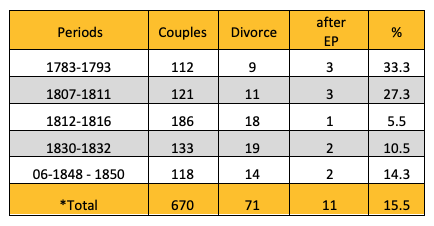

Table 5: Periods | Couples | Verdicts

In Table 5, the marriages that were divorced by verdict of the Viennese judges are brought into relation with each other in various ways. As can seen from the table, out of 670 couples whose proceedings we analyzed, a total of 71 marriages were divorced from bed and board by means of a court verdict. 11 of them (15.5%) only after lengthy evidence proceedings, which, as shown in Table 6, with one exception, were carried out by the women. With regard to the time periods, it is noticeable that the judges ordered evidence proceedings much more frequently, particularly in the first years of secular jurisdiction, than in the later periods. This result is to be interpreted above all against the normative background that contested divorces were hardly possible until 1811.

3. Verdicts after evidence proceedings

Table 6: Verdicts after Evidence Proceedings | Gender

Table 6 lists the final VERDICTS after evidence proceedings. In a quarter of the cases, the judges concluded that the plaintiff spouse had failed to provide the required evidence of marital misconduct. The dismissal of the case meant that the plaintiff spouses (four women and one man) had to resume marital life if they themselves did not want to be found guilty of “malicious abandonment”.

Among the “lost” evidence proceedings, are also those for the above-mentioned annulment of marriage which were carried out by Katharina Hakl.

Judge Hofman refused to annul the marriage. In the motives for the verdict of 13 December 1784, he argued that neither the witnesses, nor the report of the medical faculty gave any indication of the husbands impotence:

“That Hackel could by no means be called or declared to be incapable, it is also untruthful that his sexual organs have been eaten up by lust poison and are misshapen.” (WStLA 1.2.3.2.A6 Sch. 1, 13/1784)

Andrea Griesebner, January 2021, translation Jennifer Blaak