The files produced in the context of matrimonial proceedings are preserved neither from the Viennese nor from the Passau consistories. However, the negotiated matrimonial affairs could still be reconstructed using the protocol books of both ecclesiastical courts, which are now located in the diocese archive in Vienna.

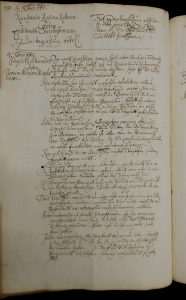

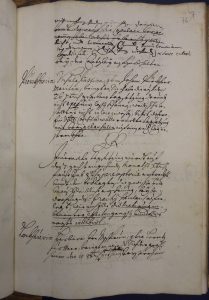

The practice of the ecclesiastical courts before 1783 therefore was investigated using the surviving “consistorial minutes”, often bound in thick folios, of the Passau and Viennese Consistories.

23. November 1674, PP 52_76r

4. Juli 1770, PP 184_147

4. Juli 1770, PP 184_418

6. September 1715, WP 120, 84v-85r

WP 25_864

Linking the Data

As already explained, the minutes of the matrimonial proceedings were not bunched into a dossier, but rather documented in chronological order in the record books, and therefore had to be reconstructed from parts into a whole. All relevant entries were transcribed, and the Latin sections (ca. 10%) were translated into German by the staff of the research project in full text according to an agreed-upon set of transcription rules.

Parallel to the investigation of the matrimonial proceedings we developed a data base, which we also tried to use at the beginning of the research process in order to aid us in our attempt to reconstruct the individual procedural steps of one proceedings. In research practice this method proved to be impractical, due to the fact that an entry in the data base required a knowledge of the respective matrimonial proceedings which we did not have at that time.

In the end we decided to use the alphanumeric outline provided by word processors as a methodological tool for reassembling entries on individual couples. In order to use the function efficiently we gave each individual entry a standardized heading that provided each couple with a common married name and recorded the date of the entry and the bibliographical information.

The greatest difficulties resulted from the surnames, since until well into the 18th century the married parties often did not share a surname. In addition to this many of the proceedings we investigated involved couples where one or both of the parties had previously been married, sometimes even more than once. Since, in contrast to the case with women, the surname of a man doesn’t change from the time of birth until the time of death, we decided to differentiate between the various marriages using the women’s names. Even though the sources often used the women’s surnames from birth or from previous husbands, we always used the surname that the woman had from the husband with whom she was legally married in the course of the matrimonial proceedings. For example, using this system, an entry regarding Maria Katharina Vogtin would be given the following heading:

Jungwirtin (born Vogtin) Maria Katharina | Johann Georg 1664-12-05 DAW PP 86_318v. The heading is made up as follows:

- Surname and First name of wife

- First name of husband

- Date of protocol entry

- Signature of record book and page or folio

The alphanumeric sorting of the headings allowed us to electronically bring all investigated entries on one given married couple into chronological order.

The chronological reading of all transcriptions on one particular married couple showed us that the couples not only carried out successive matrimonial proceedings, but that some were also involved in one or more additional proceedings simultaneous to the ongoing main proceedings. In order to be able to differentiate between the various proceedings, we compiled knowledge on procedural law. The lack of research literature on this topic made it necessary for us to gather our information primarily from court practice and contemporary treatises. We owe special thanks to our cooperative partner Karin Neuwirth, who supported us in the development of a classification system for the various types of proceedings and for the interests presented by the plaintiffs.

Andrea Griesebner, 2016, translation Jennifer Blaak.

Last update May 2020.